The Pineapple Express storms that hit California last December were the largest since January 2008. The joke going around the Bay Area was that the first thing San Franciscans do when a big storm is coming is think up a new hashtag; #hellastorm apparently took top place.

Looking at the number of patents that have been invalidated in the six-plus months since the Supreme Court’s decision in Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank [1], the only thing that adequately describes the situation is #Alicestorm.

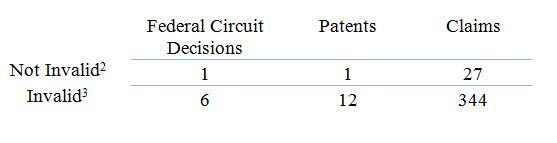

Since Alice was issued on June 19, 2014, here’s what the Federal courts have done:<a title="" name="_ednref2" [2] [3]

New Federal Circuit judges Taranto (on panel in buySafe, Content Extraction, Planet Bingo) and Hughes (on panel in buySafe, Digitech, Planet Bingo) appear to have aligned with judges Prost, Bryson, Dyk, Lourie, Reyna, and Mayer in taking an aggressive and restrictive stance on patent eligibility.

The district courts have been active as well:

The District of Delaware accounts for eleven of the lower court invalidity decisions, with the Central District of California close behind with ten.

December, 2014 was particularly “stormy”: 11 patents (858 claims) invalidated compared to 4 patents (159 claims) not invalid.

Of particular interest is that ten patents were invalidated on a Rule 12 motion to dismiss/judgment on the pleadings (or a motion to dismiss was affirmed by the Federal Circuit); by comparison only five patents survived such motions. That’s a significant outcome since on a Rule 12 motion the court must find that there is find no “plausible” interpretation of the claims to save the patent. Those courts that denied Rule 12 motions focused on this factor, and the need for evidence to support such an argument. For example, in Card Verification Solutions, LLC v. Citigroup Inc., [4] the court denied Citigroup’s motion to dismiss saying that it was a “plausible interpretation of the patent” to require a computer to perform the invention, and that “[t]he question whether a pseudorandom number and character generator can be devised that relies on an algorithm that can be performed by a human with nothing more than pen and paper poses a factual question inappropriate at the motion to dismiss stage.” Decisions like Card Verification Solutions suggest that a patentee may be able to defeat a Rule 12 motion by demonstrating that there are factual questions that need to be addressed, for example as to the scope of the claim. However, merely asserting that claim construction is necessary appears to be insufficient to preclude a Rule 12 motion or a motion for summary judgment. [5] Rather, the patentee must show how the outcome of the patent eligibility question turns on the claim construction question. For example in Cloud Satchel, LLC v. Amazon.com, Inc.[6] the court could “not find that claim construction would alter the outcome of the court's analysis even if the court were to wholly embrace plaintiff's proposed claim constructions.”

While business method patents (23) constituted the majority of the patents that were invalidated, the types of technologies ranged widely, including 3D computer animation (2), digital image management (7), document management (10), and medical records (2), database architecture (2), and networking (4). This suggests that the courts are aggressively expanding the zone of “abstract ideas” from the fundamental “building blocks” of “human ingenuity” that the Supreme Court has focused on in Alice, to just about any technological field.

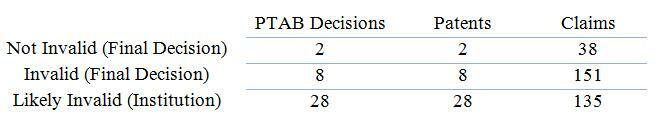

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board has also been very active since Alice:

Batten Down the Hatches

The Supreme Court in Alice said:

At the same time, we tread carefully in construing this exclusionary principle lest it swallow all of patent law. At some level, “all inventions . . . embody, use, reflect, rest upon, or apply laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas.” Thus, an invention is not rendered ineligible for patent simply because it involves an abstract concept.[7]

As the Court instructs, patent claims that “integrate the building blocks into something more … pose no comparable risk of pre-emption, and therefore remain eligible for the monopoly granted under our patent laws.” Thus, any analysis of eligibility must seriously evaluate the “risk of preemption.”

Given the numbers, I would say that the Federal Circuit, many of the district courts and PTAB have not taken the “tread carefully” part too seriously. Instead, they are rushing quickly into what Federal Circuit Judge Plager in MySpace, Inc. v. GraphOn Corp.[8] called the “swamp” and “murky morass” of Section 101. In many cases, the preemption analysis has either been ignored, or given mere lip service.

For example, in Digitech Image Technologies, LLC v. Electronics for Imaging, Inc. the court considered claims directed to storing color management information for printer and other digital imaging devices; the information was generated by specifically disclosed equations. Judge Reyna wrote that “[w]ithout additional limitations, a process that employs mathematical algorithms to manipulate existing information to generate additional information is not patent eligible.” Preemption is not even mentioned by the court. In Planet Bingo, LLC v. VKGS LLC, the court held that the claimed computerized tracking of a bingo player’s preferred bingo numbers and game cards “consists solely of mental steps which can be carried out by a human using pen and paper.” Again, the court ignores the preemption analysis entirely. The same is true in Ultramercial, Inc. v. Hulu [9], but with an added kicker: limitations that the court previously found to preclude the claims from preempting the abstract idea are suddenly deemed, without explanation, insignificant data gathering. See, The Day the Exception Swallowed the Rule: Is Any Software Patent Eligible After Ultramercial III?

And at least some of the district courts are following the Federal Circuit’s lead in ignoring the preemption analysis. For example, in McRO, Inc. v. Activision Publishing, Inc. [10] the defendants admitted that the patent claims did not cover the animation methods they used, and the court stated that “[i]t is hard to show that an abstract idea has been preempted if there are non-infringing ways to use it in the same field.” Yet the court abandoned these concerns with preemption and went on to find the claims ineligible.

Taken at face value, holdings like these set up the argument that many software or computerized process would be ineligible because they can be reduced to mathematical expressions or other functions that can be computed by a human—regardless of whether the claims actually pose any risk of preemption. By removing preemption from the analysis, the court can decide for itself what counts as significant, even though there are no facts in the record to support this conclusion. When preemption no longer matters, a court can reach any patent eligibility outcome it desires, even if there is no risk of preemption, let alone the disproportionate level of risk that is the Supreme Court’s concern.

Second, by avoiding the preemption analysis, the courts are able to rely upon doctrines that the Supreme Court has never specifically endorsed. For example the Supreme Court has not invalidated a patent under the “mental steps” doctrine merely because a human could possibly compute the result of an algorithm or equation. The mental steps doctrine arose in the early 20th century, prior to the invention of computers, for claims that necessarily required, in their own terms, human judgment and decision making. See, e.g., In re Bologaro [11] (method for setting lines of type using a mathematical procedure to determine average number of spaces per line not patent eligible; no disclosure of any machine for performing claimed method); Don Lee v. Walker [12] (method of determining the weights and positions of counterweights on engine balance shaft not patent eligible; no disclosure of any apparatus to perform the necessary calculations). These examples are a far distance from the kinds of patents now being invalidated by the courts.

A few courts seem to have gotten the Supreme Court’s message. In particular, Judge Pfaelzer, in her detailed opinion in California Inst. Of Tech. v. Hughes Comm’ns Inc. [13], writes that “A bright-line rule against software patentability conflicts with the principle that “courts should not read into the patent laws limitations and conditions which the legislature has not expressed.” Judge Pfaelzer correctly identifies themes in the Supreme Court case law: “First, the concern underlying § 101 is preemption,” and “[s]second, computer software and codes remain patentable. The Supreme Court approved a patent on computer technology in Diehr and suggested that software and code remain patentable in Alice. The America Invents Act further demonstrates the continuing eligibility of software. Moreover, Alice did not significantly increase the scrutiny that courts must apply to software patents.” In addition, she noted that “Federal Circuit precedents [after Alice] likewise offer little guidance for this Court to follow,” and specifically rejected an interpretation of “Digitech [that] would eviscerate all software patents, a result that contradicts Congress’s actions and the Supreme Court’s guidance that software may be patentable if it improves the functioning of a computer.” Judge Pfaelzer specifically criticizes the McRO decision, arguing that its approach “would likely render all software patents ineligible, contrary to Congress’s wishes.”

Beware the Undertow at the USPTO

In early December, 2014, the USPTO issued its revised “2014 Interim Guidance on Patent Subject Matter Eligibility” [14] setting forth its interpretation of the Alice and recent Federal Circuit cases, and supplementing the initial guidance published the week after the Alice decision. Buried near the end of the Guidance is the statement that “it should be recognized that the Supreme Court did not create a per se excluded category of subject matter, such as software or business methods, nor did it impose any special requirements for eligibility of software or business methods.”

USPTO Technology Center 3600 contains the electronic commerce art units 3620, 3680 and 3690, including finance, banking, health care, insurance, incentive programs and couponing, pricing, and business administration. Using Patent Advisor, I analyzed the status of 13,400 applications pending in these three art units.[15] Since Alice was decided, the allowance and issuance rate in this these art units has dramatically plummeted from about 47% pre-Alice to about 3.6% post-Alice. I found 162 patents that had issued since Alice—but the vast majority of these were based on pre-Alice allowances. In particular, I found no patents that had overcome a post-Alice Section 101 rejection. One explanation could be that it is simply too soon for such patents to have issued, given the amount of time it takes the USPTO to issue a patent after the issue fee is paid. To address that possibility, I reviewed over 150 applications what were allowed or had a paid issue fee, and again found none that had overcome a post-Alice Section 101 rejection. On the other hand, 1,463 applications had been abandoned since Alice, and over 10,000 had final or non-final office actions. Perhaps the guidance against “special requirements” should be moved to the beginning of the Guidance.

#Alicestorm is just beginning. A search of Docket Navigator indicates that there are approximately fifty Section 101 motions pending (some may be consolidated, but that would leave at least 40).

If the above-described trends continue, we’ll see at about 60% of these and future motions granted. Similarly, the outlook at the USPTO for ecommerce patents specifically is not promising: in reviewing the prosecution data from Patent Advisor, I found that 17% of the examiners (with 1159 cases) have not allowed a single application since Alice.

As one current meme has it: Winter is coming.

[1] 573 U.S. __, 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014).

[2] DDR Holdings, LLC v. Hotels.com, L.P., No. 2013-1505, 2014 U.S. App. LEXIS 22902 (Fed. Cir. Dec. 5, 2014).

[3] buySAFE, Inc. v. Google, Inc.,765 F.3d 1350 (Fed. Cir. 2014); Content Extraction and Transmission LLC v. Wells Fargo Bank, N.A., No. 2013-1588, 2014 U.S. App. LEXIS 24258 (Fed. Cir. Dec. 23, 2014); Digitech Image Techs., LLC v. Electronics for Imaging, Inc., 758 F.3d 1344 (Fed. Cir. 2014); Planet Bingo, LLC v. VKGS LLC, No. 2013-1663, 2014 U.S. App. LEXIS 16412 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 26, 2014); Ultramercial, Inc. v. Hulu, LLC, No. 2010-1544, 2014 U.S. App. LEXIS 21633 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 14, 2014); Univ. of Utah Res. Foundation v. Ambry Genetics Corp., No. 2014-1361, 2014 U.S. App. LEXIS 23692 (Fed. Cir. Dec. 17, 2014).

Prior to Alice, Taranto's first patent eligiblity decision was Smartgene, Inc. v. Advanced Biological Laboratories, SA., No. 2013-1186 (Fed. Cir. Jan. 24 2014), in which the panel--Taranto, Dyk, Lourie--ruled that an expert system for selecting complex medical treatment regimens for HIV and other diseases was ineligible as merely performing mental steps of doctor.

[4] No. 13 C 6339, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 137577 (N.D. Ill. Sep. 29, 2014)

[5] See, e.g., Bascom Research, LLC. v. Facebook, Inc., No. 12-cv-06293-SI, slip op. at 7 (N.D. Cal. Jan. 2, 2015) (“Bascom has not shown why claim construction is necessary to determine whether the patents claim patent-eligible subject matter.”)

[6] No. 13-941-SLR, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 174715 (D. Del. Dec. 18, 2014)

[7] 134 S. Ct. 2347, 2354 (citations omitted).

[8] 672 F. 3d 1250 (Fed. Cir. 2012).

[9] No. 2010-1544, 2014 U.S. App. LEXIS 21633 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 14, 2014).

[10] No. 2:12-cv-10322, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 135152 (C.D. Cal. Sept. 22, 2014).

[11] 20 C.C.P.A 845 (1931).

[12] 61 F.2d 58 (9th Cir. 1932).

[13] No. 13-cv-07245-MRP-JEM, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 156763 (C.D. Cal. Nov. 3, 2014).

[14] 79 Federal Register 241 (December 16, 2014) p. 74624.

[15] Accrording to ReedTech, the Patent Advisor data lags approximately 4-6 weeks months behind the USPTO PAIR database in terms of application status. To compensate for that I checked records individually in PAIR for allowed and cases with paid issue fees to determine their current status.

A version of this article was first published by Law360 on January 13, 2015 under the headline, “A Survey Of Patent Invalidations Since Alice.”