The Tax Cut and Jobs Act ("TCJA"), enacted in late 2017, brought substantial changes to the US tax world. It changed many domestic rules but more importantly to most readers, it also made major changes to how the US taxes outbound and inbound cross-border transactions. Let us update matters and address the status of the TCJA changes one year later.

The Status of Regulations

The § 965 transition tax regulations were issued in final form in early 2019. Treasury and the IRS were fairly strict in writing these regulations as many taxpayer comments and suggestions were not adopted. While § 965 had an immediate one-time effect, there will be important ongoing issues. The one-time inclusion created large amounts of previously taxed income (now called previously taxed earnings and profits ["PTEP"]) which will have significant effects for years to come. We will discuss PTEP further below.

The § 965 one-time tax can be paid in installments. Under the § 965 regulations, those installments can be accelerated and become due earlier on the occurrence of certain events. The regulations provide in the case of many reorganization-type transactions that an agreement can be entered into to prevent the acceleration. This will become important in many corporate transactions.

Regulations dealing with the new GILTI rules are still in proposed form. Those regulations are important. The GILTI rules interact with the existing Subpart F rules, which continue in full force and effect. The new GILTI rules require substantial planning. The GILTI regulations were received favorably by most taxpayers, although there are some anti-avoidance rules that troubled many commentators. The GILTI rules will also generate a lot of additional PTEP.

The § 163(j) regulations that limit deductions for interest expense are still in proposed form. Internationally, they propose a highly complex new regime in an effort to apply the interest limitations to a US parent company's foreign subsidiaries ("CFCs"). Old § 163(j) did not apply to CFCs. The new rules have been the subject of much criticism due to their complexity. Many advisors and commentators hope that Treasury and the IRS will back off on their thought that the regulations should apply to CFCs.

The anti-hybrid rules were covered in proposed regulations and to the surprise of many include rules dealing with "imported hybrid deductions." The imported hybrid rules were derived from BEPS and the European Commission's ATAD2 rules. In another surprise, the anti-hybrid regulations package also included an expansion of the existing Dual Consolidated Loss ("DCL") rules for inbound companies. A foreign parent that makes an entity classification election to treat a US partnership as a corporation will now need to agree that the DCL rules can apply to that entity.

The much-anticipated BEAT regulations were issued in proposed form in late 2018. The BEAT rules can operate as a true minimum tax when they apply. In an important provision, services in some cases are exempt from the BEAT rules even though there might be a markup on those services.

FDII regulations were proposed in March 2019. FDII deals with export sales, more specifically, sales and licenses to a foreign person. The regulations require substantial documentation, although this was not unexpected. These regulations were generally well received.

Not unexpectedly, substantial changes were proposed in regulations addressing the new foreign tax credit rules. They are highly complex but then again, TCJA's new rules brought about a great many changes in how the US foreign tax credit system works.

Regulations were proposed regarding the new rules that require taxation when a foreign person sells an interest in a partnership that is engaged in a US trade or business. These rules were somewhat more complicated than most commentators expected. They also provide that the gain will be deemed attributable to a US office, which under the statute is a factual issue and which is the very issue on Appeal in the Grecian Magnesite Mining case.

Section 245A and PTEP

In enacting the new rules Congress intended that foreign earnings could be repatriated free of US tax on an ongoing basis. However, few taxpayers, if any, have utilized § 245A or will in the foreseeable future. The reason is that the § 965 transition tax rules and GILTI created and will continue to create substantial amounts of PTEP. Most corporate repatriations will constitute distributions of PTEP for years to come.

However, this new attention to PTEP distributions created problems of its own, namely, a distribution of PTEP creates taxable exchange gain or loss under § 986(c). Section 986(c) is not a new provision. It was enacted in 1986. Given the large amounts of PTEP, § 986(c) has been viewed by some commentators as the "500 pound Gorilla."

Treasury and the IRS have helped a bit to minimize this issue by providing that PTEP created by § 965 will trigger exchange gain or loss only to the extent that the § 965 amounts were taxable based on the tax rates under those rules. Further, they have proposed that § 965 PTEP will have a priority in the order in which PTEP amounts are distributed.

Technical Corrections

A number of the TCJA provisions need technical corrections and/or some serious rethinking. In early 2019, outgoing Ways and Means Committee Chairman Kevin Brady (R-Texas) released a discussion draft of the "Tax Technical and Clerical Corrections Act." It proposes certain helpful, and in some cases, important, changes to the TCJA. It's not clear what will happen regarding these technical corrections given the change of control in the House. The Joint Committee on Taxation ("JCT") prepared an explanation of these technical corrections dated January 2, 2019. JCX119.

Section 958(b)(4) is the most misguided of the new TCJA rules. It can cause a foreign parent company's non-US subsidiaries to become CFCs for US tax purposes. It also creates problems when a US company enters into a foreign joint venture. The one suggested technical correction that I will address is a well-intended, but seemingly further misguided, effort to fix the rule that should never have been enacted in the first place.

The TCJA repealed § 958(b)(4), thus requiring attribution of certain stock of a foreign corporation owned by a foreign person to a related US person for purposes of determining whether the related US person is a US shareholder of the foreign corporation and, therefore, whether the foreign corporation is a CFC. This unfortunate change created all sorts of tax problems. The intent was to address a perceived minor problem but the TCJA did it with a nuclear attack. It seriously needs fixing or repeal.

The proposed technical correction would restore the previous language in § 958(b)(4) as the general rule. However, it also would provide an exception for limited downward attributions that the JCT states is "consistent with the narrow intent of the [TCJA]." To accomplish this, the technical correction would enact a new § 951B that is entitled "Amounts Included in Gross Income of Foreign Controlled United States Shareholders." I will not discuss the complicated new terms in this proposed technical correction but rather will illustrate the proposed rules with five examples.

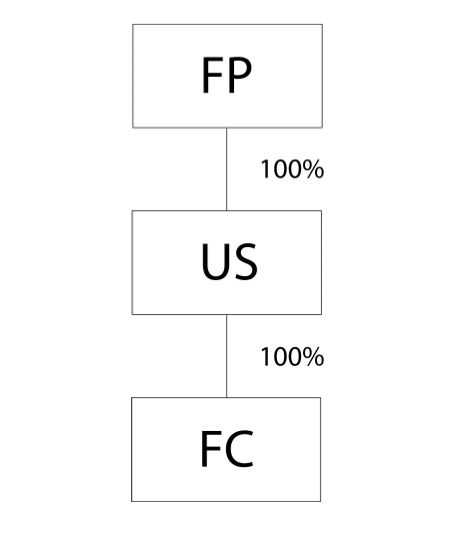

- FP (foreign parent) owns US 100% which owns FC 100%. The proposed § 951B would have no effect, here because FC is already a CFC. A CFC without the application of § 951B cannot become an F-CFC (Foreign Controlled CFC).

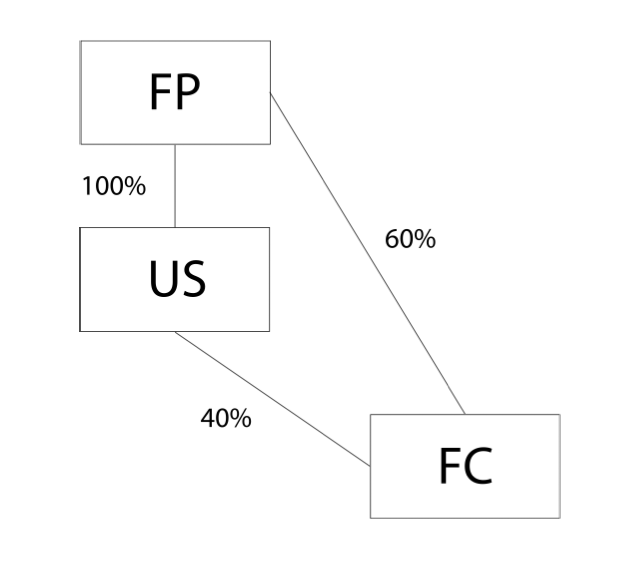

- FP owns US 100% and FC 60%. US owns FC 40%. US is an FC (foreign controlled) US SH. FC is an F-CFC. This is a change from pre-2017 law. It's the same answer as under the 2017 § 958(b) change but with important new legal terms that, for example, might affect reporting, such as F-CFC. US is taxed via 958(a) on income attributable to its 40% interest in FC.

- FP owns US 100% and FC 100%. US is an FC US SH. FC is an F-CFC. Same answer as under 2017 change but with different legal terms, as in #2.

- An outside US Investor example: FP owns US 100% and FC 90%. X, an unrelated US corporation, owns the other 10% of FC. Under the TC, US is an FC US SH and, as to US, FC is an F-CFC. Proposed new § 951B operates "with respect to" US and FC. As to X, X is not affected by what happens to US. As to X, FC is not a CFC, and pre-2017 law is restored.

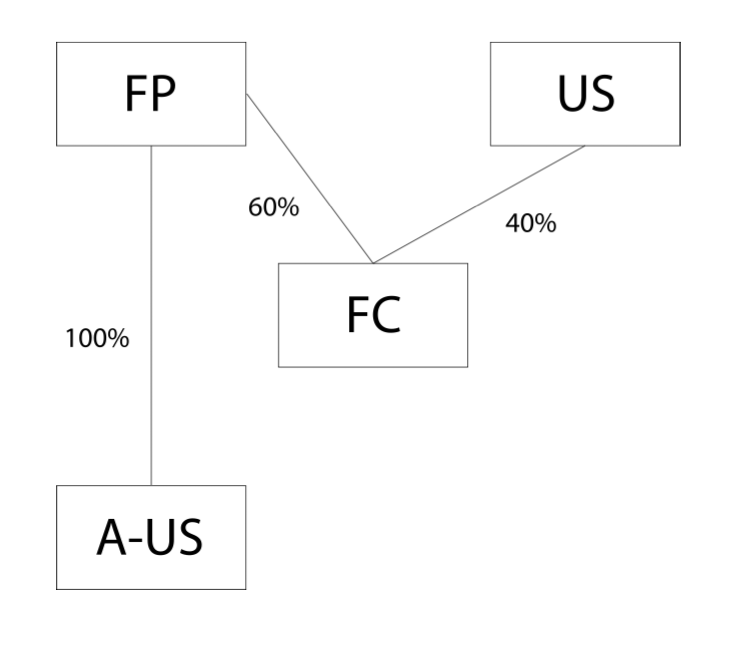

- A JV example: US owns 40% of FC (a JV entity). US has no foreign ownership, so it cannot be an FC US SH. FP, simply an unrelated foreign corp in this example, owns 60% of FC (the JV entity) and 100% of A, a US Corp. Section 951B does not operate regarding US since it's not an FC US SH, so pre2017 law is restored as to it, and as to it, FC is not a CFC or an F-CFC. Section 951B does operate regarding A, an FC US SH, and thus FC becomes an F-CFC, but only as to A.

Open questions include reporting (e.g., Form 5471), not for US in Example 5, but for A. However, A already has this issue today, that is, if the technical corrections were not enacted. Presumably, the regulatory authority under § 951B(d)(1) would be used by the IRS to resolve reporting matters for A. The same issue arises in Example 4 for US The IRS has already addressed this informally today in reasonably similar circumstances.

The amendments are proposed to apply to the last taxable year of foreign corporations beginning before January 1, 2018, and each subsequent taxable year of such foreign corporations and taxable years of US persons in which or with which those taxable years of foreign corporation's end.

Originally published by Expert Guides on March 20, 2019.